“Cards are the sign manual of society. Their use and development belongs only to a high order of civilization. They accompany us, as one writer has justly remarked, all the way from the cradle to the grave. They begin with engraved announcements fo the birth of a child, then cards for its christening, and, later on, dainty little cards of invitation for children’s parties, until in due time, the girl crosses that line “Where the brook and river meet Womanhood and childhood sweet,” sets up a card of her own, and blossoms forth into a young lady.”

Social Etiquette by Maud C. Cooke, 1899

We discussed the act of calling, but let us pause for a moment and discuss the calling card itself.

“The personal, or visiting, card is the representative of the individual whose name it bears. It goes where he himself would be entitled to appear, and in his absence it is equivalent to his presence. It is his “double” delegated to fill all social spaces which his variously-occupied life would otherwise compel him to leave vacant.”

Etiquette by Agnes H. Morton, 1917

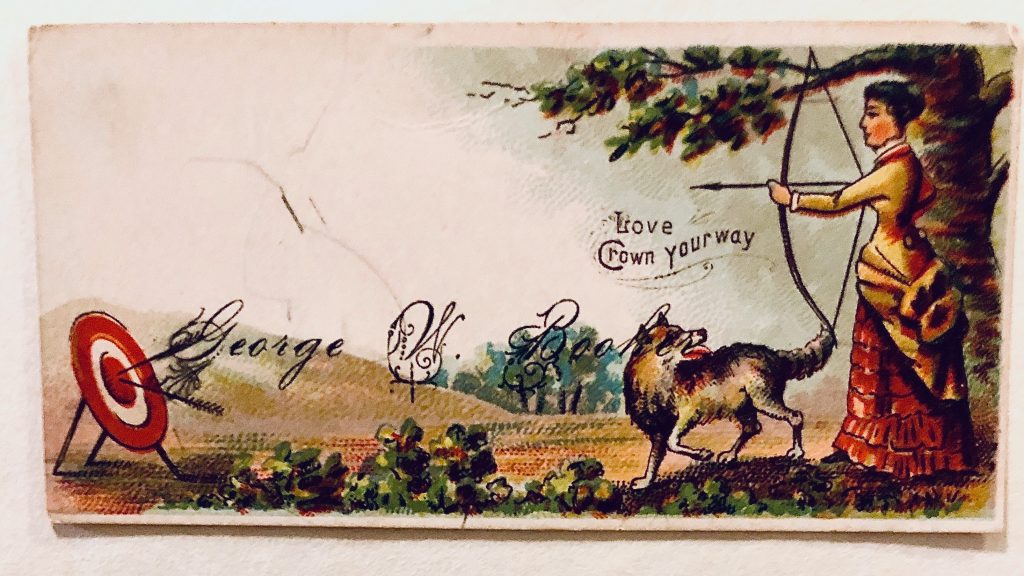

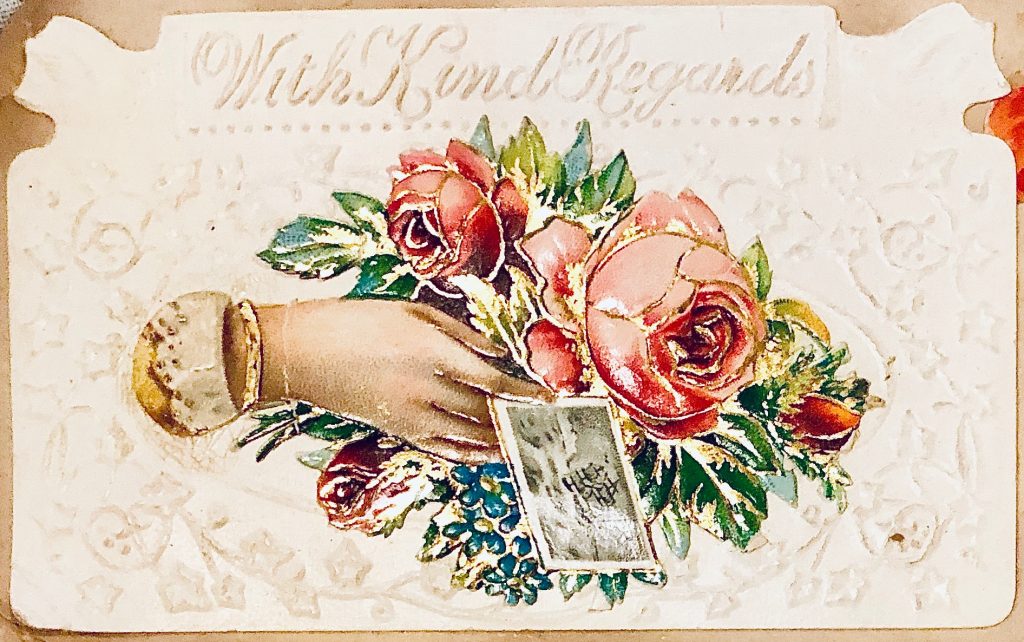

It is said that calling cards, (also known as visiting cards) go back in their earliest form to 15th Century China, but it was 17th Century France that codified the practice and 19th Britain that made it a common practice among more than the elites. The explosion in calling cards is directly related to innovations in printing. First with simple printed cards with the bearers name on it. Followed by breakthroughs in color printing which allowed for a wide variety of designs. This meant you could have seasonal designs, designs to be given to members of the opposite sex, etc.

Victorians were not like us in that they did not actually perceive a class difference between engraving and printing. Printed calling cards were new and cutting edge technology, so that often trumped the cost and craft of letter pressed or engraved cards. Of course, the more elaborate and finer the printing, the more expensive the card and the greater impact on the person receiving it. Some cards had concealed names and others bore the photograph of the person in question. By the turn of the century, the fashion for garish cards had faded and the calling card returned to engraved or printed cards with just the bearers name on it.

Cards were a way of keeping record of who attended an “At Home”, but it was also a way of letting people know you had come when they were not there. A servant would take a calling card and place it on a silver tray in the front hall. The idea was that the receiver would collect the cards when returning home and then know who had called when they were out. This would also let them know to whom they owed a call. Often cards were left on the silver tray so that others could see what thrilling people had come to your house. It was very like the 19th century version of letting everyone see the likes on your instagram page.

Calling cards were also used to relay sentiments such as congratulations, get well and with deepest sympathy. While the members of a house in mourning might not be receiving visitors, it was seen as a comfort to be given a stack of cards from your friends and acquaintances expressing their condolences.

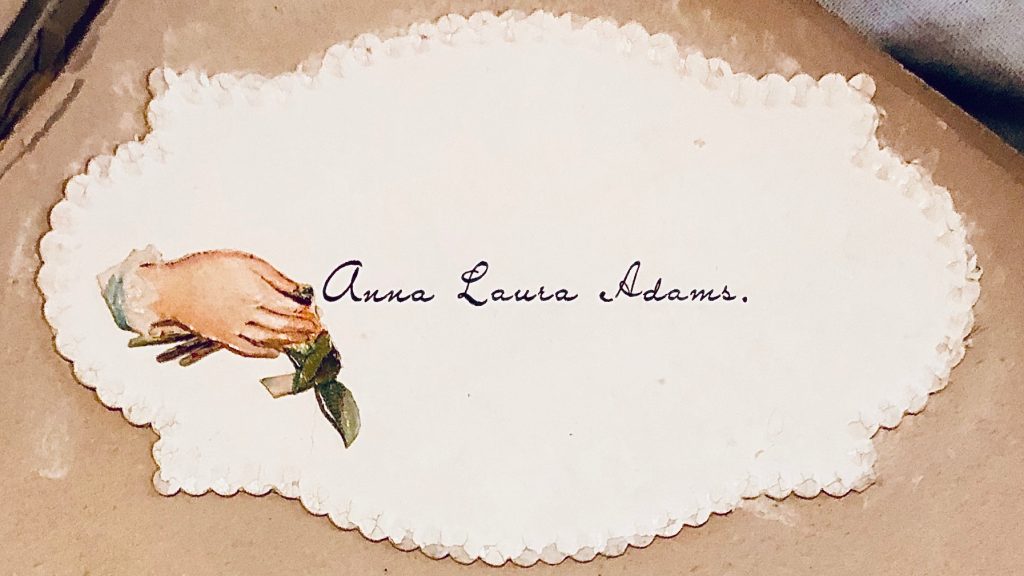

Outside of design, calling cards followed fairly strict rules. A lady’s card would be 2 3/4 to 3 1/2 inches by 2 to 2 3/4 inches, while a gentleman’s card was 3 to 3 3/4 inches by 1 1/4 to 1 1/2 inches. The differing dimensions meant that you could see at a glance the type of social visits you were receiving. Depending where you lived, married and unmarried women might have different sized cards. The same for men. The size of cards also went through fashions depending on the year and the season. If you want a post on the size instructions for calling cards, let me know.

Ladies were the ones to leave cards at a house. Yes that’s right, cards, plural. Two cards would be left, one for the gentleman of the house and one for the lady. A married woman might leave three cards, two of her husband’s card and then one of her own. The thinking was a man’s card would go to both the wife and husband of the house being visited, while the woman’s card would only be of interest to the woman of the house. There are not many places until the late 1920’s that it would have been acceptable for a woman to leave a card for a man in a social setting. Women could leave cards for their lawyer, doctor, etc. but these were considered business calls and even they strained the limits of propriety in some circles. This does vary by area, as some etiquette guides in major cities state that a woman should leave two cards, but etiquette guides for less cosmopolitan areas indicated that she should only leave one.

Married women could go calling by themselves, but single women could not, rather they would go with their mother, an older female family member or chaperone. A brother might do in a pinch, if ones mother had passed away and the young lady was now mistress of her father’s house. These rules varied from country to country, city to city and even town to town. It was social suicide not to know the rules of ones own patch. In these cases, a single lady would leave her card as would an aunt or brother. Chaperones often did not, it depended on the social circumstance of the woman doing the chaperoning.

The woman of the house was also the one to accept the calling cards. No doubt it was considered beneath the master of the house to concern himself with such trifles. Often the card was left on a tray in the entrance hall that was put there for that purpose. If no one was home, a card could be left at the door to show that you called.

If one was not invited to a lady’s At Home, a card could be left on an alternate day. Having paid your respects, one might expect an invitation to call or to attend the next At Home. If no invitation was forthcoming, the card-bearer could assume they had been slighted, this could lead to years of animosity between women. While this might seem trivial, this could effect social standing and even a husbands business prospects. Each step was to be thought out carefully and strategically.

If there was a set “at-home” day and you were told by the butler that the lady was not a home, this could be seen as a tremendous snub if no excuse was given. It was also considered in the worst possible taste for the woman of the house to snub someone who made a visit, unless you had very good reasons, as this was tantamount to “cutting dead”.

If there was no printed sentiment on the card, a note could be added relaying the intention of the call. In the middle and late Victorian periods, folding different corners of a card meant different things. The Victorians loved codes of all sorts, from Fans and Parasols to Stamps and Calling Cards. Every detail relayed some tidbit of information. This fell out of favor by the less freewheeling Edwardian period.

Calling cards began to fall out of favor in the Edwardian period. Some say it was because of the penny postcard, but it also has to do with changing mores and attitudes towards the leisure class. After the first world war, not as many people could get by without working and increased taxation hastened this shift. People no longer had the time for endless rounds of “At Homes” and calling.

By the twenties, calling cards were only seen in very specific settings. The practice of giving calling cards to high school and college graduates continued well into the late 20th century. These were exchanged as a memento of your classmates in the way that autograph albums were once used. Though very few people bought the calling cards when I was in high school, preferring to write messages on the back of school photos. I was recently informed by a young friend that as of the 2010’s, class rings and calling cards are no longer “a thing”. I wonder if this is true everywhere.

Now-a-days, you’ll really only see business cards, which are very much the working class version of the calling card. Indeed, we are back at a time when business cards are like their Victorian calling card counterparts, a tool for self expression. Many have designs, colors and photographs on them, once again driven by new technology. I’ll cover business cards in a later post, as they are fascinating in their own right, especially Japanese business card etiquette.

It’s easy and inexpensive to collect calling cards. They usually cost only a dollar or two a piece, unless the name on the card is notable. The older the card the more expensive they will be. Regency calling cards are particularly costly.

I truly hope we’re back to calling on friends soon. I hope you’re well. Much love, Cheri